On the first day of spring, Tuesday, March 21st, I made a bee-line from my classes in Bikfaya to prepare for a taxi ride from the Catholicosate all the way to the headquarters of the

Armenian Syrian Prelacy in Aleppo, Syria, to spend a few

days as the guest of His Grace, Bishop Shahan Sarkissian, Bishop of Aleppo and

Prelate of Syria.

Armenian Syrian Prelacy in Aleppo, Syria, to spend a few

days as the guest of His Grace, Bishop Shahan Sarkissian, Bishop of Aleppo and

Prelate of Syria.The taxi is shared and has five passenger seats, in principle, just like the service taxis common to most Middle Easter cities. Fr Krikor reserves the front two seats for me (the passenger side and the middle space between driver and passenger) and the cost for the one-way trip is $40 USD — not bad for a five hour taxi ride! Sharing the cab with me (taking the three back seats) are two Syrian Christians, both French speaking. Josef is Maronite and his business partner Jean is Armenian Catholic. Pictured here, our driver Biki, along with Josef and Jean.

The ride in goes well. Biki's a good driver and certainly knows how to make the most of the powerhouse under the hood of his white Olds. Crossing the border goes smoothly, and soon we have turned away from the coastal route to head inland to the heart of Syria.

Pictured here, the road headed east, not far from the coast — the countryside and foliage here (eucalypti) remind me of California's central coast. It takes just under five hours to drive the 400 kilometres to Aleppo, not bad given particularly the poor quality of the roads in Lebanon.

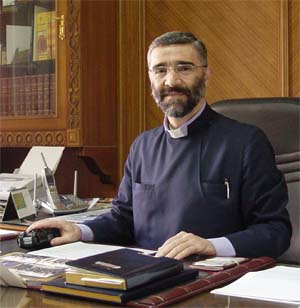

Bishop Shahan (Shahan Serpazan) is waiting to welcome me on my

arrival. He is the Armenian Prelate responsible for most of Syria — pictured

here at work the following morning. Serpazan is 43 years old and has been a bishop for

about 2 years. He served for several years as the dean of the seminary in

Bikfaya, and has also worked as a priest in Iran. I know the seminarians at

Bikfaya from Aleppo seem very fond of him, and my short time in his company

confirms that he is much loved by his people and not surprisingly, he is truly a

caring and capable man.

work the following morning. Serpazan is 43 years old and has been a bishop for

about 2 years. He served for several years as the dean of the seminary in

Bikfaya, and has also worked as a priest in Iran. I know the seminarians at

Bikfaya from Aleppo seem very fond of him, and my short time in his company

confirms that he is much loved by his people and not surprisingly, he is truly a

caring and capable man.

We have a long first conversation. He has a meeting that begins

about an hour and a half after my arrival, long enough for us to have a good

chat. Serpazan has completed the course work for a doctorate in Patristics at

Louvain (Belgium). In his spare time, which is miniscule, he works away at what

will no doubt prove a life-long project. He hopes to publish a critical edition

of a commentary on the Book Genesis, by an early 13th century Armenian divine,

Vardan Arevelci. Serpazan has gathered quite a collection of manuscript copies

of the commentary — dating back as close as 10 years from the "autographed" or

original edition. Hardly a day goes by when he doesn't find at least a few

moments for this work.

Conversation with Shahan Serpazan is easy and wide ranging.

He wants to practice his English, but in a pinch switches to very fluent

French.

Conversation with Shahan Serpazan is easy and wide ranging.

He wants to practice his English, but in a pinch switches to very fluent

French.

My room at the Prelacy is comfortable, and Serpazan a most gracious host. The Prelacy is in the heart of the old city of Aleppo, a neighbourhood that is picturesque and active.

The area is also loaded with mosques, in fact Aleppo boasts thousands of mosques, I learn - 4-5,000 in all. At 4:03 in the morning, I am jostled from my sleep by calls for the city's minarets, one must only be a few feet away from my window certainly not easy to ignore! At first the call seems like the work of a huge disorganized choir. Pictured here (above left), the times for the five sessions of daily Moslem prayer for March 22, posted at Aleppo's largest mosque. Click here to listen to a recording made from my bedside in the wee hours of the morning.

Four hours after my rude awakening, I join the bishop for a

service in the Cathedral, across the narrow old city street from the Prelacy.

Today's service begins with the normal Wednesday morning prayers, but this is

followed by a formal celebration of the mid-point in the long Lenten fast. The

old Cathedral is nearly full for the Lenten prayer service, and the congregation

is almost entirely made up of women. Serpazan gives a sermon and there is

much singing. I meet my colleagues at the Cathedral in Aleppo, including Fr. Housig

(furthest left, above, and pictured here, right) who is my counterpart,

responsible for the Cathedral in Aleppo. He is a married priest, as are all but

one of the priests in the diocese.

singing. I meet my colleagues at the Cathedral in Aleppo, including Fr. Housig

(furthest left, above, and pictured here, right) who is my counterpart,

responsible for the Cathedral in Aleppo. He is a married priest, as are all but

one of the priests in the diocese.

I learn later that the system used in Aleppo for the deployment of parish clergy allots one priest for 500 families. The Cathedral has about 2,000 families, and four priests. One, Fr. Zareh, who will be my guide for a tour of Armenian schools on Thursday morning, inherited his pastoral charge of 500 families from his father, who retired from active ministry a few years ago. Parish priests do not move around as much as they do in the Anglican tradition in North America; and tthe Armenians of Aleppo still form social groupings based on their ancestral village of origin in Turkey, and preferably with the priest responsible for a given grouping from the same village. Appointments tend to be life long, and the passing of a charge from father to son, is not unusual.

Following breakfast, my exploration of Aleppo begins in the 17th century Cathedral of the 40 Martyrs. The Cathedral is reached through a small door on Haret al-Yasmin street, across from the Armenian Prelacy where I am staying. The archivist for the Prelacy, Mihran Minassian has kindly accepted Shahan Serpazan's invitation to serve as my guide for the morning; and I couldn't ask for a better arrangement.

A native of Aleppo, Baron Mihran has lived and worked in the old city all of his profession life and knows it well. (N.B. "Baron" means "Mr." in Armenian.)

Baron Mihran takes great

pride in showing me the Cathedral. Among other things it houses a magnificent

collection of paintings, like this one on the wall to the far right (above) and

pictured here. It is perhaps the most famous painting in the Cathedral's

collection, portraying the "end time", the Day of Reckoning when Christ, supreme

judge will separate human kind as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats.

You can see, in the detail of the painting, below, the demons gathering up the

souls lost to their master waiting

Baron Mihran takes great

pride in showing me the Cathedral. Among other things it houses a magnificent

collection of paintings, like this one on the wall to the far right (above) and

pictured here. It is perhaps the most famous painting in the Cathedral's

collection, portraying the "end time", the Day of Reckoning when Christ, supreme

judge will separate human kind as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats.

You can see, in the detail of the painting, below, the demons gathering up the

souls lost to their master waiting

below, while the saints of God process triumphantly into the

new Jerusalem, eternal city of God.

below, while the saints of God process triumphantly into the

new Jerusalem, eternal city of God.

In addition to the

great last judgment panel, there are two wonderful

images of St. George, several portraits of the Theotokos (Madonna and child),

and some wonderful paintings of the Armenian saints like this one of St. Mesrop

Mashthotz, the man who gave the Armenians their distinctive alphabet in the year

401.

great last judgment panel, there are two wonderful

images of St. George, several portraits of the Theotokos (Madonna and child),

and some wonderful paintings of the Armenian saints like this one of St. Mesrop

Mashthotz, the man who gave the Armenians their distinctive alphabet in the year

401.

The Cathedral served for centuries as a way-station for Armenians

walking from their homeland to Jerusalem. Pilgrims visiting the Cathedral

would leave their mark to testify to their faith and purpose along the pilgrims

path.

visiting the Cathedral

would leave their mark to testify to their faith and purpose along the pilgrims

path.

When we leave the Cathedral, Mihran leads me through the maze of streets and alleyways to the oldest part of the city. Our destination is the Great Mosque (Al-Jamaa al-Kebir), only 10 years younger than the great Umayyad Mosque in Damascus (see earlier post, below). The mosque has yet to open when we reach its doors, so I follow Mihran for a short detour to a smaller mosque across the way that was once the Church of St. Helena dating from the 4th century.

Beside the steps leading down into the courtyard of the mosque is this last remnant of a earlier faith tradition. I am thankful for Mirhan's familiarity with Old Aleppo, as I would likely have not notice either the old mosque nor its marker were I walking through the neighbourhood on my own.

During our visit to the older building, word comes that the Great Mosque is now open, and we join the small throng gathering at its entrance. Shoes removed we first step foot in the large courtyard with its original freestanding minaret. Built in 1090, it is said to have a pronounced lean as a result of an earthquake. Lonely Planet describes the tower, "Standing 47m high, it's a beautiful thing, rising up through five distinct levels adorned with blind arches to a wooden canopy over a muezzin's gallery where mosque official calls the faithful to prayer." — one of the more powerful voices in the choir that woke me early this morning!

Inside the great prayer hall there is a "fine 15th-century carved minbar (pulpit). Behind the grille to the left of this is supposed to be the head of Zacharias, the father of John the Baptist.

Opening up to the south of the Great Mosque is the famous souq of

Aleppo, reputed to be the biggest and best in the Arab world. Mihran tells me

that there are more than 12 kilometres

of walkways like the one pictured here, twisting

and winding their way through and around the busy covered market. I've been told

that it is possible to find anything and everything one might possibly wish to

purchase in the souq, and that the shop keepers speak just enough of most of the

world's major languages to close a sale. Pictured here, a specialist in herbs

and spices, particularly those used in traditional medicine. The souq seems to

be organised, as is the wider central market area as well, according to items of

interest.

of walkways like the one pictured here, twisting

and winding their way through and around the busy covered market. I've been told

that it is possible to find anything and everything one might possibly wish to

purchase in the souq, and that the shop keepers speak just enough of most of the

world's major languages to close a sale. Pictured here, a specialist in herbs

and spices, particularly those used in traditional medicine. The souq seems to

be organised, as is the wider central market area as well, according to items of

interest.

During our explorations, we walk down a street lined with shops on either side specializing in oil cloth … the old fashion table and cupboard surface cloth based surface covering that has all but vanished from the hardware stores of North America.

Mihran worked for 17 years on an archival project located in the

heart of the souq and he knows his way through the labyrinth quite well. We stop

to buy some fresh Arab bread with thyme paste at a shop Mihran praises as

Aleppo's best; and around another corner, Mihran invites me to have a look into

the otherwise hidden courtyard pictured above — in the back, not pictured here,

there are bolts of freshly died silk draped from the balcony above to dry n the

sun. Aleppo was the major stop on the famous silk road of yore. Undoubtedly what

most impresses the western visitor to Aleppo is the fascinating array of

costumes and personalities, at times reminding me of scenes one might expect in

an Indian Jones movie. "This isn't Kansas anymore."

me to have a look into

the otherwise hidden courtyard pictured above — in the back, not pictured here,

there are bolts of freshly died silk draped from the balcony above to dry n the

sun. Aleppo was the major stop on the famous silk road of yore. Undoubtedly what

most impresses the western visitor to Aleppo is the fascinating array of

costumes and personalities, at times reminding me of scenes one might expect in

an Indian Jones movie. "This isn't Kansas anymore."

Next on my tour with Mihran of the Old City, we stop at Aleppo's famous citadel rising up on a high mound, surrounded by a moat (now dry) at the eastern end of the souq. The mound was the site of an ancient temple of the 10th century B.C. — suggesting 12,000 years of continuous habitation in Aleppo.

Despite some suggestion that the mound was first used as a fortress in the Greek period, following the death of Alexander the Great, most of the physical structure dates from the 12th century when the citadel served as the base for Moslem activity at the time of the Crusades. To give a sense of scale, those are the heads of people seen as small dots along the walk way leading to the main gate above.

The Citadel commands a vantage point over Aleppo that gives me a first opportunity to get some sense of perspective about the size of the city. The population of Aleppo was last reported to be about 2,130,000 — about 300,000 more than the city of Montreal. The population is 90% Moslem, and the Christian population is condensed into a compact area more-or-less to the upper left of the photo here.

Leaving the Citadel, we begin our return to the Prelacy, heading first

to the centre Aleppo's New City (as only a couple of centuries old.) Dating from

the beginning of the 20th century, the Bab al-Faraj clock tower stands in the

centre of what was once the glory of Aleppo, with many European styled buildings

like those pictured here. The Bab has recently become the centrepiece for a

future glory of Aleppo, with several major projects, including a classy new

Sheraton Hotel, popping up in the area. Of particular note in 2006

Leaving the Citadel, we begin our return to the Prelacy, heading first

to the centre Aleppo's New City (as only a couple of centuries old.) Dating from

the beginning of the 20th century, the Bab al-Faraj clock tower stands in the

centre of what was once the glory of Aleppo, with many European styled buildings

like those pictured here. The Bab has recently become the centrepiece for a

future glory of Aleppo, with several major projects, including a classy new

Sheraton Hotel, popping up in the area. Of particular note in 2006 , the

activities during Aleppo's turn as the World Capital of Islamic Culture for the

year are centred near-by.

, the

activities during Aleppo's turn as the World Capital of Islamic Culture for the

year are centred near-by.

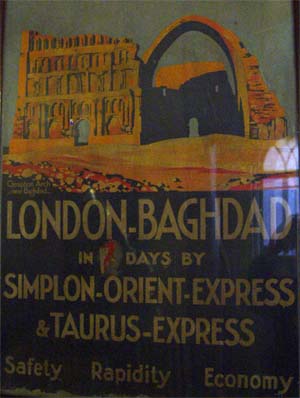

But there is another hotel than the Sheraton that attracts our interest as we complete our walking tour of old Aleppo. A few short blocks from Bab al-Faraj we reach our real goal in exploring this part of town: the gemstone of Aleppo's more recent history, the Hotel Baron. The Armenian Mazloumian family founded and continues to operate the hotel –"Baron" means "Mr.", remember? — and Baron Mihran knows the Armenian woman who has staffed the front desk for most of the past 40 years so we are taken on a tour.

"Lawrence of Arabia slept in Room 202; from the balcony in Room

215, King Faisal declared Syria's independence. The Presidential Suite was

occupied in turn by Sweden's King Gustaf Adolf, Egypt's Jamal Abdel Nasser, Syria's

former President Hafiz Al Assad, Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan (the founder of the

United Arab Emirates), and the American billionaire David Rockefeller." *

Pictured, above, the dressing table that served as Agatha Christie's workdesk as

she wrote the famous who-dunnit, Murder on the Orient Express.

Abdel Nasser, Syria's

former President Hafiz Al Assad, Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan (the founder of the

United Arab Emirates), and the American billionaire David Rockefeller." *

Pictured, above, the dressing table that served as Agatha Christie's workdesk as

she wrote the famous who-dunnit, Murder on the Orient Express.

Once back at the Prelacy, Mihran goes his way and Shahan Serpazan's housekeeper serves a late lunch she has prepare for me. I wonder when the other four lunch guests will arrive (if the size of the servings is a measure.) This is the first of several large meals I will enjoy during my stay with the Armenians of Aleppo.

Every day, back at the Catholicosate, and for more than two months now (the time is flying!) I join the community there for daily prayers at 7 a.m. and 5 p.m. in the Cathedral. Serving as deacons, acolytes and chanters, for these offices, there is a group of young men studying for ordination to the married priesthood in the Armenian Orthodox Church.

Pictured here, senior seminarians (back row left to right) Arin, Hovhannes (Johnny), Joseph, Apraham (Apo), and Harout. Front row, Joseph and Hirayr.

Seminarian Johnny (Hovhannes) is in Aleppo for a couple of days on

an errand for his teach, Fr. Vaghinag, and

Shahan Serpazan arranges

for Johnny to collect me for a late afternoon exploration of the neighbourhood

around the Prelacy.

Shahan Serpazan arranges

for Johnny to collect me for a late afternoon exploration of the neighbourhood

around the Prelacy.

The Prelacy is in the heart of the old city, and very much in the shopping district. The narrow streets are lined with shops and the product line that seem most prominent in the area is clothing and accessories (handbags, etc.) for women. There are also several shops with clothing for infants and small children; and there is a steady flow of Moslem women shoppers throughout the day in the neighbourhood.

Other product lines concentrated in a specific areas near the

prelacy include car parts, butcher shops, furniture stores and even the

occasional workshop like this smithy stall a few corners from the Cathedral.

workshop like this smithy stall a few corners from the Cathedral.

The Moslem weekly holy day is Friday, and most Syrians work the other six days of the week. Christians will keep Sunday as their day off, if business or profession allows, with work on Fridays and the other days of the week. Government offices are closed for a weekend of Friday and Saturday.

In recent years, an effort has been made to improve the image of the neighbourhood and a few trendy restaurants and boutique hotels are beginning to appear.

Johnny knows his way around the neighbourhood quite well.

He tells me

that he shared his father's business for a few years before deciding to enter

the seminary and train for the priesthood. He is stoic about the immediate

future. He must marry before he can be ordained a priest — orthodox priests are

not allow to marry once they are ordained, even a widowed priest must be

celibate if he wishes to remain a priest, or he must renounce his orders and

become a layman if he decides to marry again. Shahan Serpazan has confirmed that

Johnny is a candidate for ordination as priest, so now "all he has to do" is

find himself a wife! Johnny reflects that being the wife of a priest is not easy

and not every girl would be happy in this role.

He tells me

that he shared his father's business for a few years before deciding to enter

the seminary and train for the priesthood. He is stoic about the immediate

future. He must marry before he can be ordained a priest — orthodox priests are

not allow to marry once they are ordained, even a widowed priest must be

celibate if he wishes to remain a priest, or he must renounce his orders and

become a layman if he decides to marry again. Shahan Serpazan has confirmed that

Johnny is a candidate for ordination as priest, so now "all he has to do" is

find himself a wife! Johnny reflects that being the wife of a priest is not easy

and not every girl would be happy in this role.

We walk around for a couple of hours, visiting his father's shop and the shops of his two uncles. Johnny's father is a wholesaler for consumer electronics, one of his uncles has the local Sony boutique, and the other uncle works in air-conditioning and refrigeration.

The shops are open from mid-morning until quite late at night. This seems to be the pattern for most people I meet in Aleppo, late mornings and later nights, with shops closing around 10 or 11 p.m. and most, including clergy, going to bed after 1 or 2 in the morning.

After our walk, Johnny borrows his father's car and we drive out to see the university and some of the new and trendy development projects in Aleppo.