May 2, 2006 - Post No. 71

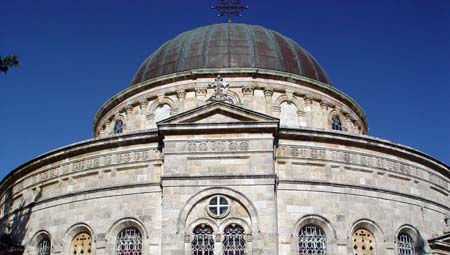

A short walk takes me to the edge of the ultra-orthodox (Jewish) neighbourhood to the north of the old city in the large general area that is known as New Jerusalem. My destination, the beautiful Ethiopian Orthodox monastery of Däbrä Gännät, home to a small community of Ethiopian monks and nuns. On entering the walled monastic enclosure, a couple of the monks greet me warmly and extend an invitation to have a look inside the church.

It is a beautiful building, completed in the early 1900s thanks to

the generosity of a French aristocrat. The sanctuary, with its curtained

doorways, is a church within the church, and stands at the centre of the

building. A circle of columns rising to support the main cupola of the

church surrounds the towering sanctuary aedicule,

creating

an ambulatory or outer circle divided into sections, with white wooden and glass doors, for the clergy and for the people.

creating

an ambulatory or outer circle divided into sections, with white wooden and glass doors, for the clergy and for the people.

The icons in the church are quite lovely, including two depicting the legendary exploit of St. George who, as reported in the post "Day in the City", is an Arab saint, traditionally a native of the region that is now downtown Beirut.

English crusaders enamoured with St. George's example of saintly chivalry (note a maiden in distress to the right of St. George) adopted the saint's cult and imported it to the British Isles where St. George would eventually become the patron saint of England and his flag (blood red cross on a white field) the emblem of the English nation.

Surrounding the square sanctuary aedicule and supporting the cupola, is a circle of twelve pillars -- a model of the Biblical New Jerusalem in the neighbourhood, it is interesting to note, that is called by that very name. Over each pillar one of the twelve Apostles of the Lamb.

Surrounding the high dome of the sanctuary aedicule, the icons of the patriarchs and major prophets ... Moses can be seen in the photo above.

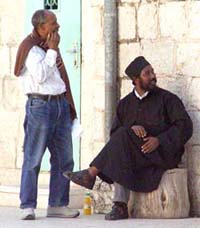

After

visiting the church, I return to the courtyard of the monastery deciding

to wait for the daily service of Vespers which takes place at 5 p.m. ...

which means in about 30 minutes. I find a block of unclaimed stone and,

much like the one the monk in the picture here is sitting on, and settle

down to enjoy what is really

a lovely spring afternoon in Jerusalem.

After

visiting the church, I return to the courtyard of the monastery deciding

to wait for the daily service of Vespers which takes place at 5 p.m. ...

which means in about 30 minutes. I find a block of unclaimed stone and,

much like the one the monk in the picture here is sitting on, and settle

down to enjoy what is really

a lovely spring afternoon in Jerusalem.

The courtyard is alive with the come and go of monks, nuns, and the faithful, and as the hour for Vespers draws near, several from the small Ethiopian community in Jerusalem begin to gather.

I'm not sure how many of the half dozen or so women here today are nuns, clearly not all of them are. This woman (pictured, above) wears a white shawl as do all of the women here, and the shawl is also worn by many of the Ethiopian men. The white shawl may serve to recall the sacrament of baptism, but regardless, it can certainly be considered a liturgical vestment of sorts, worn for the offices and liturgies of the church. Wearing ceremonial vestments is not limited to the clergy in the Ethiopian tradition.

The

woman in the picture (above) is seen approaching another woman (lower

right corner, and pictured here), and she does so with all the

ceremonial courtesy one might expect would be reserved for a

bishop ... bows and a ceremonial embrace (a triple kiss, back

and forth, of the other's left and right shoulders.)

The

woman in the picture (above) is seen approaching another woman (lower

right corner, and pictured here), and she does so with all the

ceremonial courtesy one might expect would be reserved for a

bishop ... bows and a ceremonial embrace (a triple kiss, back

and forth, of the other's left and right shoulders.)

There is a wonderful calm in the courtyard. At first I wonder whether I might not make use of the time before the service to explore the surrounding neighbourhood, but in the end it seems best to simply enjoy the relaxed atmosphere of the Ethiopian monastery's enclosure.

The Ethiopians are welcoming and friendly, and I soon enjoy a few pleasant conversations including one with a monk who is curious to learn about Canada. He asks what kind of animals we have in Canada, "Lions, tigers ... elephants?" I respond that, no, the animals of Canada are quite different and I tell him about deer, moose and bears.

He also tells me that there are seventy Ethiopian monks and nuns living in Jerusalem, in 10 monastic houses ... the most problematic of these, the rooftop monastery at the Church of the Resurrection -- simply because the conditions there are so poor.

Soon it is time for Vespers and, wearing my cassock for this visit, I am invited to join three Ethiopian monks in the chancel area before the main door of the sanctuary -- the laity gather, unseen from the chancel, on another side of the sanctuary aedicule.

The Ethiopian office of Vespers begins with something reminiscent of the synagogue services I have attended, in that each of the priests seems to be saying his own prayers aloud, and each at his own speed.

After about 15 minutes of this jumble of psalms and canticles, the monks stand and begin chanting. Now the singing seems intentionally separate, and the chants work as a kind of canon or round. One monk begins singing, then the second, then the third. Click here to see a short movie (20MB) which gives you an idea of the singing.

Both clergy and lay Ethiopians lean on long sticks (pictured above) with ivory T-shaped handles, to support themselves during the lengthy periods of standing in Ethiopian worship -- they really only sit when there's a sermon. The lay folk also use the sticks in a kind of rhythmic ritual dance during parts of the Divine Liturgy, pounding the stick to the ground, then sweeping it up into the air.

Part of the Ethiopian piety includes balancing on one foot for long periods of time (see the monk above clothed in a white shawl.) One of the lay women tells me that they must stand through all of the two hour Divine Liturgy as part of their preparation to receive Communion, and monks are known to stand, balancing on one foot for hours at a time, not only during services, as a kind of spiritual discipline.

Finally, the service concludes when one of the priests dons a cope and the priestly breastplate or stole of the Orthodox traditions, holding a hand cross, while another reads the Gospel. Then the priest offers the closing blessing and final prayers. At one point in all of this, he turns slowly around a couple of times in some sort of ritual gesture.

The service lasts a bit more than an hour; and I am thankful for a great sense of peaceful calm that has come over me as I leave the monastery courtyard for the return trip to the Armenian Patriarchate.

Directly across from the walled monastery, this lovely Arabian balcony with its typical triple gothic window arrangement. I can't help but think of Fr. Nabil and Sarah Shehadi in Beirut, and their observations on the traditional design of Arab houses (see the post, "Steps to Mar Nicholas") This home might have belonged to one of the displaced Palestinians in the Arab language congregation at Fr. Nabil's Anglican church in Beirut; but it is definitely Israeli now.

As I approach the popular Ben Yehuda Street district, I walk past this group of security workers who will be helping with the crowds expected to descend on to the street for an outdoor concert and fireworks this evening. Israel's Independence Day begins at sunset tonight with festivities planned throughout the country.

It's still relatively quiet on Ben Yehuda Street, the cafés and bistros are only beginning to fill, and the many boutique owners are no doubt hoping for lots of shoppers among the many expected for the evening's festivities.

I've come to know this part of town fairly well over the past couple of weeks -- it's a good walk from the old city. There are a couple of descent bookstores, a great falafel stand, and I've even succumbed on one occasion -- mea maxima culpa! -- to the temptation to sample a hamburger at the MacDonald's here.

Nearing the old city, I walk by one of the trendier housing developments of New Jerusalem -- as upscale as any that one might expect to find in the major North American or European cities, and only a short walk from the ramparts of Old Jerusalem.

Pictured here, the nearby minaret of 1655 and the Citadel Museum at its base, also known as the Tower of David. The Citadel was built in the 16th century by Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent on the remnants of the Herodian fortress where, tradition holds, Pontius Pilate condemned Jesus to scourging and the cross.